Taking Possession

Present day Shelby checking in to say: I am okay. Re-reading these essays has been a study of time and emotion. When I was writing, I wanted it to be sincere. I wanted to protect myself from judgment. I wanted the salacious details to only exist in your imagination. But the writing now is striking me as “woe is me.” I keep reminding myself that these are genuine reflections of how I felt. I did feel screwed. At one point I was paying rent at two places at once. And I’m not sure if this is clear— but I was pissed off. Sadness and anger occupied equal parts of my mind and often fed each other. This constant heightened state, paired with an extreme hyper-vigilance left me exhausted. I was afraid everywhere. I was angry everywhere. I was sad everywhere. And while most of these intensities have subsided, to some degree, there is still that deep resonating chord that cannot be unheard, unfelt. I am less angry, less sad, less hypervigilant. This stain occupies my own memory. I seek the spotless mind. The intrusive thoughts, the what-ifs, are specters who find me in the night humming that chord.

In the attempt to understand what has happened to me and how I have responded to it, I have scoured popular media to find modalities for re-telling. What I find most compelling about these fiction and non-fiction retellings is the variation of form and method yet there is a commitment to seeing, reenacting. And in my limited personal reference library, I have mostly seen people impacted by violence tell their stories like that of court testimony—with and without an actual trial.

Echoes of trial procedure can be found in the materials of my work. The bed sheets and the photographs are evidence, the castle in the sky is painted with my fingerprints, and this could be considered a kind of impact statement.

Testimony as the model of re-telling felt like the only model that would garner attention, and maybe to some degree care. And the response, from what I witnessed, was a different kind of trial in the social court. The public, now consumers of testimony, would volley and bat around the details and determine, with no evidence, judge, or jury, if the impacted person was complicit or an innocent victim. (See also: The Ideal Victim) And before I sound too superior, I do this too, with mundane reality television, scripted dialogues and stories, and news articles with detailed yet flat retellings of complex crimes.

Participating and witnessing this, time and time again, became incredibly distressing when it came time for me to write. Why would I offer testimony when there is no trial? With no trial, there is no glimmer of accountability, let alone justice. Still, I want to talk. I want to build upon this growing modality resource— one that doesn’t rely on reenactment with every microscopic detail available for dissection. I have even found solace in anonymous Reddit AMAs.1 Solace is recognition. When someone describes an emotional or psychological experience that I can relate to, that feels very specific to my experience, I feel seen, understood, like I don’t have to offer further explanation. It’s like an internal pressure valve releases.

I saw Greer Lankton’s work at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Encased in Plexi was a puppet. Jackie O with her pink pillbox hat. The miniature Jackie’s human hair was perfectly curled. The hat sat askew, perched, on her head. Her face had cheekbones sharp as razors and in her hand was a red bouquet. She was frozen mid-strut.

Lankton’s work is so painfully sincere. Jackie had delicate and fearsome femininity.

Through mixed media and paper-mache dolls and sculptures, Lankton created and re-created the body. At the same time, she was forming and reforming her own body as she transitioned, experienced drug addiction and body dysmorphia.2 When Lankton died, photographer Nan Goldin wrote, “There was absolutely no distance between her life and her work."3

Goldin continued, writing that she was “more instinctive than cerebral, more physical and visual than verbal, her work was her form of communication.”

Her permanent installation at the Mattress Factory, titled “It’s All About ME, not you,” is a recreation of her studio. Surrounded by her dolls, large and small, some dismembered and mounted, some surrounded by pill bottles, the viewer is left to decode.

In “Unalterable Strangeness,” Andrew Durbin writes, “I’ll resist the obvious by stating that I don’t think Lankton’s work reflects a turbulent or tortured sense of her own body, despite her dolls’ sometimes turbulent and tortured nature. Rather, their re-visional quality suggests a distinctly queer and trans experience of the world, one that is attentive to physical mutability and the rotation and flexibility of 'roles.'"4

Goldin mimics this interpretation writing, “[…] she gave birth and rebirth to herself through dolls.”5

Without Lankton, viewers are left with the archive— her drawings, paintings, writing, and dolls. Their open mouths are echoes of the source.

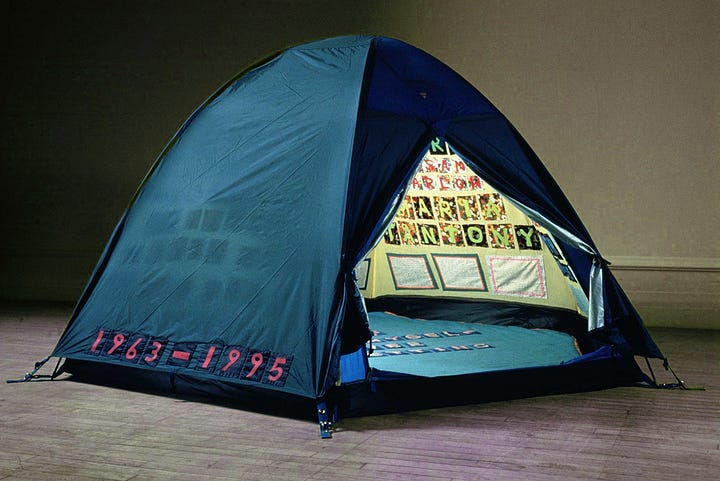

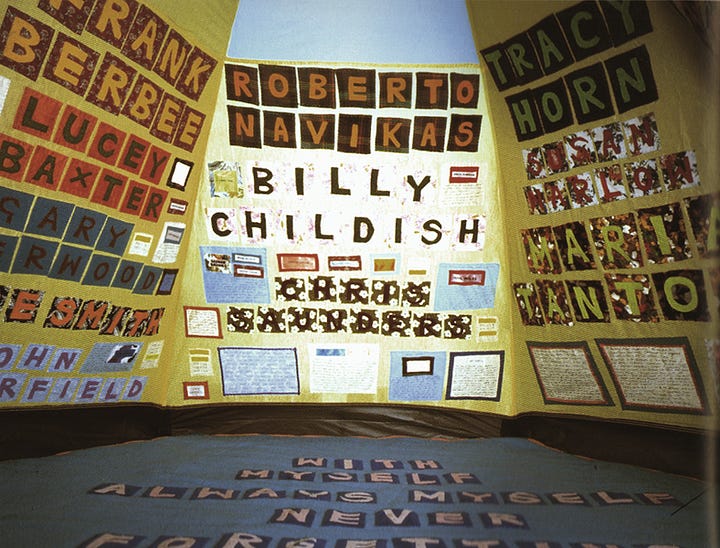

In the realm of making the interior exterior, I also consider Tracy Emin’s work, “My Bed,” featuring the real detritus of her life, and domestic space, displaying the impacts of deep emotional pain on her immediate environment. And the now-destroyed, “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With,” tent featuring the names and descriptions of platonic and intimate relationships. Burned in a fire, Emin has refused to recreate the work, leaving it in collective memory and documentation.6 The ephemerality of these works uses time as a framework, presence and reflection as material, and the labor of reckoning with the seen and unseen as concept.

At the Hayward Gallery in London is, “The Woven Child,” an exhibition dedicated to the fiber and soft sculptural work of Louise Bourgeois. The bodily forms, hang, drape, and are contained in various metal and glass sculptures. The nearly 90 works were primarily made in the last 20 years of her life.7 Using materials from her own home, she preserves a few as hanging works and the rest are torn and rejoined as bodily and abstract forms. This process then reconnoiters “the dualities between the physical body and the psyche, the conscious and the unconscious, and the potential for both fragmentation and reparation.”8

For the Hayward, Tracey Emin reflects on her friendship with Bourgeois, noting her persistent dedication to her own artmaking while also living through and near art historical movements and figures like Monet and Picasso. 9

Emin continues, “It wasn’t just like a basic art object to fill a space within the realm of art, it was another aspect of her mind that was coming out. When you work like that, it’s timeless.”10

Bourgeois herself said, “All my work in the past fifty years, all my subjects, have found their inspiration in my childhood. My childhood has never lost its magic, it has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama.”11

In Intimate geometries: the art and life of Louise Bourgeois, Robert Storr charts the life and work of Bourgeois. He writes:

Bourgeois's art was shaped not only by primordial symbols but by the pent-up energy of the past. The objects she created are vessels for that energy, places in which she might safely store and reflect upon it. Each represents her effort to render a specific psychic force in a physical form and so master it, thereby transforming terrible anger or doubt into a tolerable, albeit provisional, order and certitude.

He continues, “For her, making something was a way of taking possession of that which possessed her.”12

For example: “I (32f) am a survivor of child sex trafficking and torture, AMA.” The poster answers several questions about their experience. These two quotes especially resonate: “I've come to terms with the fact that this is not my secret--it is theirs. And I don't want to keep it anymore.” Later they write, “Honestly, it's that I don't want to be ‘recovering.’ I can't get on board with the language of it being a journey. A journey sounds fun, I'd love a nice adventure! But I just want quiet. I want peace. And I want to be allowed to be broken and vulnerable, without being pitied. I don't want to have to heal. It sounds very juvenile, but it isn't fair that I'm the one left to do all of the hard work of finding a way to live happily. Idk if that makes sense.” It makes complete sense to me, OP. link here

Goldin, Nan. “A Rebel Whose Dolls Embodied Her Demons.” New York Times. December 22, 1996, sec. H. accessed April 23, 2022. https://login.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/rebel-whose-dolls-embodied-her-demons/docview/109602587/se-2?accountid=4840

Ibid

Durbin, Andrew. “Unalterable Strangeness.” Flash Art, April 30, 2015. https://flash---art.com/article/unalterable-strangeness/.

Goldin, Nan. “A Rebel Whose Dolls Embodied Her Demons.” New York Times. December 22, 1996, sec. H. accessed April 23, 2022. https://login.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/rebel-whose-dolls-embodied-her-demons/docview/109602587/se-2?accountid=4840

Takac, Balasz. “Inside That Tracey Emin Tent of Everyone She Ever Slept With.” Widewalls, January 21, 2020. https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/tracey-emin-everyone-i-have-ever-slept-with.

“5 Things to Know about Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child at Hayward Gallery.” Southbank Centre, December 20, 2021. https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/blog/articles/5-things-to-know-about-louise-bourgeois-woven-child-hayward-gallery.

Ibid

Tracey Emin on Louise Bourgeois. Southbank Centre, 2022. https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/blog/videos/tracey-emin-on-louise-bourgeois.

Ibid

Stoops, Susan L. “Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child (in Context).” Worcester Art Museum, October 21, 2006. https://www.worcesterart.org/exhibitions/past/bourgeios.pdf.

Storr, Robert. Intimate Geometries : The Art And Life Of Louise Bourgeois. New York, New York: The Monacelli Press, 2016, 31.

Bourgeois is quoted, saying, "Work was a kind of a balancier... a pendulum, and it guarantees that you are a sociable being. It is a guarantee that the artist is not going to do unsociable things."