swallowed, like a play on consumption, a place where I talk about art sometimes

Y’all know the recently trending girl math. (Not to be confused with girl dinner.) But let us not forget that the girls have been mathing. For example, in the 1940s a “kilo-girl” was how many women, literally computers, it took to, well, compute.

From Computing Power Used to Be Measured in ‘Kilo-Girls’:

“By the time World War II broke out, many scientists and industrialists in the U.S. were measuring computing power not in megahertz or teraflops, but in ‘kilo-girls.’ And computing time was measured, in turn, in ‘girl hours’ (with complex calculations requiring a certain amount of ‘kilo-girl-hours’).”

Despite the long and significant history of girl math, 1992’s Teen Talk Barbie, preloaded with a variety of phrases, announced, “Math class is tough!” Barbie, mostly Mattel, was heavily scrutinized for perpetuating beliefs that math, and being good at it, is somehow fundamentally gendered. Even so, the controversial plastic teenager generated necessary conversation on the systems that excluded women from STEM fields, despite their long history in computing and mathematics. Barbie has had 250 different careers and counting. (Notably none of which has included motherhood.)

Barbie is a mirror, reflecting what society does and does not care about or, at least, what it will purchase. Barbie, in my own girlhood adolescence, was an acrobat beautician, a mom or a sister, a girlfriend or too busy to date. Mattel does not design or limit the individual imagination, fantasy, or play. And when I learned that Barbie said math class was tough, the part of me that struggled in math class did feel recognized.1

A show title like Girl Math, while simple in phrasing, and on-the-surface analysis would appear to be trend hopping, is an opening to a series of questions around girlhood, systems, gender, mass-produced objects, history, and play.

On Saturday, March 2nd Capitol Hill Arts Workshop (CHAW) hosted the opening reception of Girl Math with artist Sarah Jamison. According to her artist statement she utilized “images sourced from the public domain and personal tokens; these objects operate as both symbol and narrative in her work.”

The paintings, primarily made using colored pencil, acryla gouache, and ink, are composed with a central figure, ranging from object to creature, in an expanse of coordinating color. Variations include barbed wire and chain link fencing, each severing to reveal the central figure.

In one is a pastel cherub, or putto, with blue, red, and orange textural highlights. The cherub gazes off, avoiding eye contact while wings splay out around it. The figure, traditionally used to recreate the nativity scene had the “height of its complexity and artistic excellence in eighteenth-century Naples.”

In Jamison’s rendition, the cherub hovers at the center, surrounded by a chain link fence, perhaps miraculously cut away to reveal the cherub on soft, blurred blue cloudy skies. The chain link itself is rendered in blue matching the sky and disappears and reappears as it contrasts soft, white clouds. The piece is titled, Second Highest Order of the Ninefold Celestial Hierarchy. The second of the hierarchy, girlhood, and the pre-established pop culture references call to mind the lyric, “Always an angel, never a god” from the boygenius song “Not Strong Enough.”

Other pieces center mass-produced objects, like a vending machine sparkly alien ring, or a yellow smiley face sticker with an unexpectedly straight-lined mouth instead of an upward curve.2 While some might consider this collection an exploration of nostalgia, Girl Math could also indicate the transformation that occurs when a mass-produced object enters the personal realm and suddenly becomes precious, symbolic, and sometimes powerful.

The largest work features a brass letter opener with a unicorn head. It is suspended above a blurred field of daisies, rendered soft and hazy. In contrast, the detailed and worn, unicorn opener shines. It is titled, An Interpretation of “The Unicorn Rests in a Garden.”

The work is a direct reference to the historic and beloved Unicorn Tapestries. The magical creature fused to a tool in conversation with the tapestry depicting a unicorn that could escape, but perhaps chooses not to, generates a compelling line of questioning.

Here are a few:

Wouldn’t a magical creature, like a unicorn, become a tool through capture and training? And wouldn’t a creature captured and trained find safety in an escapable cage, in loose chains? What is choice when not every option can be perceived? And for Jamison’s work, the Unicorn fully alchemized into a brass letter opener, a tool, is set free. Floating there, above the blurred daisies, the unicorn is again an object or ornament. This figure, imbued with centuries of fantasies, still finds space in contemporary lives to continue a long line of wondering.

A final piece, notably sequestered from the others, is a black heart. On it, are small white dots mimicking a clear night sky. In the top right corner is a white hand, with red-orange fingernails, holding their keys in a fist. In between each finger is a key and a plastic-stained glass key chain hangs from the curved fingers. The piece is titled, Call Me When You Get Home. This might be the most overt calculation. While the other works allow for ambiguity and viewer perspective, this work is an obvious narrative of the fear and anxiety felt on a late night, going home.

The works, some pastel, some more vibrantly hued, are the fractals of girl-ness3 floating in varying scenes allowing visitors space to conversate, project, interact, and discover. Sure, they could be nostalgic at the surface, but willing examiners might open to the infinitely complex.

For Dessert…

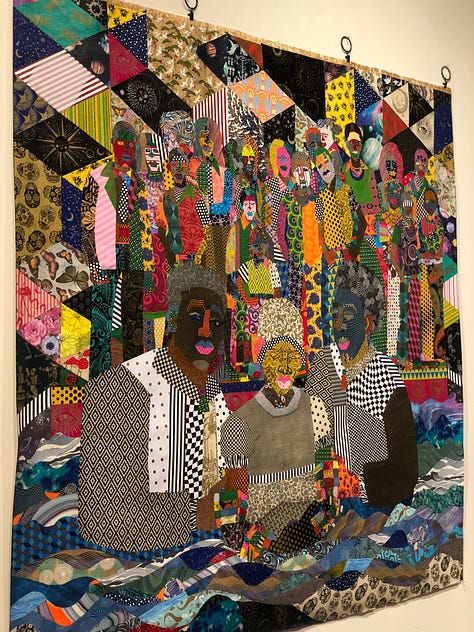

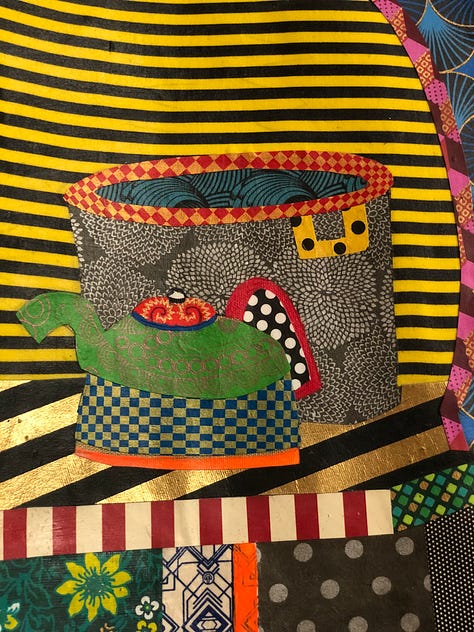

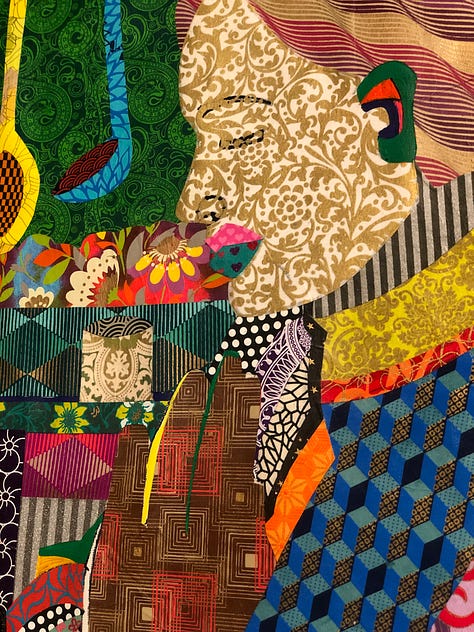

GATHER/TOGETHER by ZSUDAYKA NZINGA TERRELL & JAMES STEPHEN TERRELL at the Y Gallery

If you’re in the DMV area, consider making a stop at the YMCA. I went for the artist talk and watched the artist/couple interview each other learning intimate details about their process and DC art history. The work felt and is important. I couldn’t believe I was seeing it at the local gym — and yet this level of causal community access is relevant to the experience of the work. The photos I took are terrible — just go see it for yourself.

It’s eight stories of artists taking over an abandoned corporate office building, room after room filled with artwork sometimes by three different artists. I described it as walking through TikTok. I was captured by the rooms that remained empty, or filled with discarded desks. The empty rows of bookshelves, and more quiet artistic interventions. And I already staked my claim on one piece and might go back for more. Collect local art! Opening night appeared to be successful, but if you missed it, fear not. You have a few more weeks to see the corpse of corporate America devoured by the colorful, local artist-cultivated mycelium.

On the menu…

Bucolia by MK Bailey at Transformer

An immersive examination of The Garden as a site of both immense beauty and tragedy, Bailey's installation uses quietly terrifying gardenscapes as the backdrop for complex, dreamlike narratives.

Twin Snakes in the Ameri-Cognitive Dissonance by Anthony Le & Ashley Jaye Williams at Culture House

These paintings and sculptures are an attempt to unpack modern society’s many Frankensteins — with their giant cacophonous vision boards for the modern hellscape.

Homecoming (I’m Coming Home) by February James at Cultural DC

This showcase is a tribute to where I first learned and how I learned to care for myself—the place where the behaviors that form part of my identity were meticulously crafted. Exploring relationships between personal identity, space, and time, this exhibition offers a nostalgic reflection on the transformative journey from adolescence to adulthood.

Going straight from public school education, where I floundered in math and science classes, I found myself in community college remedial math. The teacher, Mr. Hammock, taught math in a way that was finally understandable to me. I couldn’t believe it after struggling for, up until that point, my whole life. In elementary school, we recited times tables, and with every number set we recited correctly our name would move around the room. My name got stuck and I could never perfect the recitation as my peers bounced by. This continued until community college and I finally caught up. I excitedly signed up for his class again the next semester and I remember him working through proofs to show us why the math was ( yes, I’m gonna say it) mathing. I would come home, sit in the silence of an empty dining table, and do my math homework willingly, watching the numbers and equations unfold, finally a solvable game. He told me to take trigonometry with him next semester, that I would love it. But I moved. I became a caregiver from my grandparents and enrolled in the nearest college. Wanting to feel the numbers slip through my fingers like silk again, I enrolled in trig. I failed. The only class I ever failed in college. I drew doodles on the exams, relinquishing the power I once felt, to once again accepting that I would never be good at math. How easy it was, to slip back into this role of being incapable. Even I knew there were some classes I shouldn’t have passed in middle, high, and even elementary school. I tried tutoring and going to my professor for help, but the language of numbers eluded me once again. And the doodle I drew would make it to my professors’ door, proudly scanned, copied, and displayed. It depicted something like a funeral scene with a stick figure holding a box, descending into the long line where the solution was meant to be. The small box contained the hope I had to pass the test.

Vending Machine Sparkly Alien Ring is the name of a band I’m starting right now, don’t steal it, thanks

Girl, in my usage, is not tied to the features of a physical body, but to experience, feeling, understanding, and interior parts recognized.

What should I devour next?